From Scotland to Namibia (via Mönchengladbach)

by Brian Robson

From Scotland to Namibia (via Mönchengladbach) Brian Robson Like many amateur game authors I used to dream about having a game published one day. But the demands of real life all too often obstruct the best laid plans … a lack of available time for playtesting and development, combined with an uncertainty over how – or if – any of my designs would be received by publishers, led me to just keep on dreaming … maybe one day …

The announcement of the Mücke Spiele game design competition on www.spielmaterial.de in September 2008 spurred me on to do something about my own inertia and I started working on some ideas with a view to pushing myself (and my long suffering gamer friends) into developing, testing and submitting a game for the competition. The big question was … where do I begin?

Unlike my previous (mainly untested and under developed) designs which were not constrained by concerns such as the number and type of pieces and available themes, the competition criteria forced game authors into using fairly specialist pieces from the Kosmos game Giganten in their design. In some ways this constraint made the game design process somewhat easier, as it channelled the flow of the creative process and limited the design options.

From Scotland to Namibia (via Mönchengladbach) Brian Robson Like many amateur game authors I used to dream about having a game published one day. But the demands of real life all too often obstruct the best laid plans … a lack of available time for playtesting and development, combined with an uncertainty over how – or if – any of my designs would be received by publishers, led me to just keep on dreaming … maybe one day …

The announcement of the Mücke Spiele game design competition on www.spielmaterial.de in September 2008 spurred me on to do something about my own inertia and I started working on some ideas with a view to pushing myself (and my long suffering gamer friends) into developing, testing and submitting a game for the competition. The big question was … where do I begin?

Unlike my previous (mainly untested and under developed) designs which were not constrained by concerns such as the number and type of pieces and available themes, the competition criteria forced game authors into using fairly specialist pieces from the Kosmos game Giganten in their design. In some ways this constraint made the game design process somewhat easier, as it channelled the flow of the creative process and limited the design options.

I already had the supply / demand / price movement market mechanism in my head before I started work on Namibia. This arose from observing the British economy during 2007/08 where overoptimistic overstocking by many stores in the UK led to deep discounting and cheaper goods for shoppers. It struck me that although this was not a sensible way to run a business (or a national economy), it would make an interesting game mechanism.

I also didn’t want to enter a game about oil into the competition. I guessed that most of the competition submissions would have an oil theme and wanted to develop a game which told a slightly different story. Given that the derricks were one of the main components I thought that mining would work well.

Why Namibia? Firstly, it is somewhere I have wanted to visit for a long time … Etosha National Park, Fish River Canyon, the Sossusvlei sand dunes, the desert elephants … the list goes on. Being Scottish, I like to visit places where there is not so much rain. Secondly, and more importantly for the purposes of the game, Namibia is a major exporter of minerals so it fitted the mining theme quite well. And as a bonus, the shape of Namibia, with its north-eastern promontory, makes for an interesting map.

So I had the theme, the setting and the market mechanism; the next job was to try to put this together into a game which worked. I already had an outline game design (only a few ideas jotted on a page) for a game of railway development and resource collection in colonial South Africa. So I borrowed some of these ideas and worked them into the first version of Namibia.

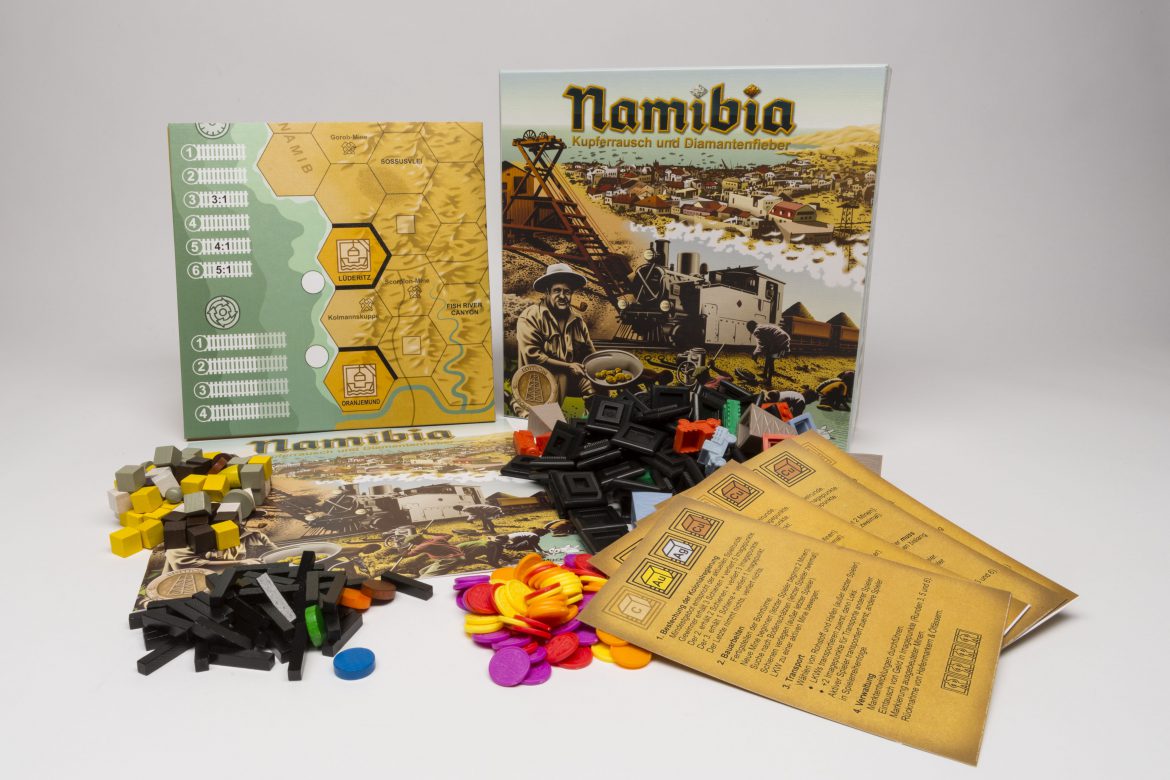

The most technically difficult aspect of the initial design process was putting together a map of Namibia made up of hexagons. I managed to obtain a satellite photo of Namibia from the internet and, after much trial and error, overlay a hexagonal grid. My Paint Shop Pro and Microsoft Publisher skills were pushed to the limit and the resulting map was huge – four pages of A3. But it was useable and managed to survive the playtest sessions with mercifully few changes.

Putting the rules together was much more challenging. As anyone who has ever attempted to put a ruleset together will tell you, it is more difficult than you can imagine to translate what appears to be a fairly simple concept in your head into a clear and unambiguous statement in a document. Thankfully, one of my gaming friends is a legislator at the Scottish Parliament and he is very good at pointing out ambiguities and inconsistencies. We were on version 0.3b of the rules by the time we reached the first playtest.

For me, it is important to have a complete set of rules for the first playtest. They don’t have to be attractively laid out with images and examples (version 0.3b was a simple Word document), but it does help players understand what is expected from the game, and from their participation in the game. It also forces you, as the game author, to ensure that you have covered all eventualities and closed any loops within the game system before anyone else has the chance to pass comment.

The first playtested version of the game was far too long and complex. Players scored reputation separately for each commodity making the administration of scoring and pricing difficult. The market was also a bit static and needed some changes to stimulate movements. In addition, the game was 12 turns long resulting in a playing time of somewhere between 4 and 5 hours! Not good. So it was back to the drawing board to simplify the game and shorten the playing time. The most memorable playtest comment was “there’s a game in there somewhere” … now I just had to find it and draw it out.

I should probably say something here about criticism of your game designs by playtesters. It can be very difficult at first to hear your friends say a lot of negative things about your latest creation in which you have invested a lot of time, energy and emotion. The first time one of my games was playtested I ended up feeling really defensive and a bit hurt … but experience shows that playtesters are usually right, particularly about what doesn’t work well within a game design. Good, constructive, negative criticism is a vital component of the redevelopment / retesting process and should be greatly valued. (As an aside, our gaming group playtests the annual Fragor games release. You would not believe the negativity of some of our criticism … but it is all because we want to see a good game emerge at the end of the design and development process.)

Version 0.4a of the rules was the next version to be tested. This simplified the construction and shipping phases but left the scoring intact. The game was speeded up a little but would still come in at around three and a half hours. Cash was only converted into reputation points once at the end of the game and players still scored reputation separately. “It flows better, but is still too long and complex” was the main feedback.

Version 0.5 shortened the game to 8 rounds, introduced a staggered cash to points conversion system and simplified the reputation scoring into the single scoring system which is implemented in the final game. Adding the score track to the board took me a long time! Version 0.5a made the auctions more difficult by removing the discounts for second and third places (previously players paid 2/3rds and 1/3rd of their bids, respectively). The game was now clocking in at around the two hour mark for the experienced playtesters. When I asked “is it good enough for the competition” I was told “go for it!”.

By this stage the competition entry date was fast approaching and some largely minor, final cosmetic tweaks were made to the game files before I packaged them up and sent version 0.6 to Mücke Spiele.

When I submitted the files for Namibia to the competition – one day before the submission deadline! – the best I was hoping for was some constructive feedback on my design from the Mönchengladbach gamers to enable me further develop my game design capabilities. I was overjoyed to reach the playoff stages (the last 8 … better than Scotland have ever achieved at the World Cup!) and very, very surprised when it was announced that I was one of the joint winners of the competition.

The e-mail from Harald Mücke telling me that I was a joint winner of the competition said “don’t spend all of the prize money on champagne”. I followed his advice and bough a good bottle of single malt scotch whisky instead.

At that stage I naively thought, in the best superhero tradition, “my work here is done”. Wrong.

Herr Mücke started to ask lots of questions resulting in a fair old bit of work for me … can we have an administration summary to ease players through the administration phase? … can we cut the number of game rounds? … can we change the map? … could we add Namibian landmarks to the map?

So the game was reduced to 6 turns and “no go” areas surrounded by pre-built rails were introduced on to the map and the map size was reduced. This had the unexpected side effect of making some of the players’ choices more difficult. The rail building action had more options and the prospecting action was now much more tactical and required more thought.

The last set of changes arose when the final version of the board began to be developed by the artist, Carsten Fuhrmann. The size of the board was limited to 400mm x 400mm so the map was compressed and the “no-go” areas removed. The price range of the market was also reduced from a maximum of 20 down to 15 so that the market index could fit on to the board. We weren’t sure how the map and market would now play out but were very pleasantly surprised when we playtested the game. The playtesters all felt that the shorter, more compact map improved gameplay by forcing more player interaction and making some of their choices more difficult. The game still clocks in at just under 2 hours and this is put down to the “additional thinking time” now required by players.At the time of writing we’re still going through the final development phase. An additional end of game market movement has been introduced (to increase the impact of the final prospecting actions) and the final English version of the rules is being reviewed.

I have – rather cheekily, it has to be said – proposed a Namibia expansion to Herr Mücke. The expansion introduces another commodity (uranium) which is prospected, shipped and valued differently from the other commodities mined in the game. The board includes the a price track and starting spaces for the uranium ore. To find out how this works you’ll need to go and buy the game!

So to all of you readers who, like me, dream about having a game published one day, please don’t give up. It is not easy, and you’ll need the help of your fellow gamers to playtest your designs (and you’ll need to listen to their criticism of your “baby”), but it is well worth persevering. Believe me. If I can do it – so can you. Of course, now I dream about having another game published …

My wife tells me that I’ve been as excited as my 4 year old son at Christmas during the final development phase (since the artwork started appearing) and I’m getting worse as Spiele ‘10 at Essen approaches. I must admit I’m just enjoying the ride and trying to learn as much as I can from the experience.

I would like to thank Harald Mücke for being patient with me, a very inexperienced game author, throughout the development and publication process. I hope he finds that publishing Namibia is well worth his time and effort.